Roadmap To New Organizational Territory

Training & Development Journal - June 1988 - By Bill Veltrop and Karin Harrington

There's a new breed of organization emerging, one whose culture is based on commitment rather than control over people. You've heard of some of these; you may also know that there are over 100 of these innovative organizations throughout the United States and Canada.

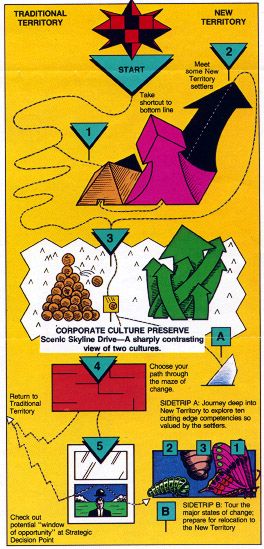

After a focused inquiry into some of these organizations, we created a "roadmap" into the new territory of large-scale change or transformation in these organizations. Following this roadmap, you-and especially your CEO-can decide if the new territory warrants further exploration.

A Scenic Tour Through Two Territories

What are "new territory" organizations? Why move to the new territory? Who else is there? What special skills does it take to get there and stay there? What forces drive cultural change? How can this change be successfully managed?

These are some of the questions we determined to answer in a focused inquiry into organization-wide transformation efforts. This was a practitioner-to-practitioner inquiry about successful, major change projects. We also talked with theorists and organization leaders at the cutting edge of this work. In all, we spoke with over 100 resources that described a variety of approaches being used in over 25 companies.

Follow the route on the Executive Roadmap, and check out these points of interest along the way.

1. The Bottom Line: differences in results between traditional organizations and commitment-based organizations.

2. Meet some New Territory settlers: the organizational pioneers in the new territory.

3. Skyline Drive: a drive along the ridge between a typical traditional organization and a composite hypothetical, commitment-based organization.

Sidetrip A (see page 30) departs here: an exploration of 10 cutting-edge leadership competencies essential to achieving and sustaining a culture of high commitment.Veltrop is principal of Bill Veltrop ~ Associates in Soquel, California. Harrington is an associate with tbe company.Training and Development Journal, June 19884. The Maze of Change: some of the forces driving cultural change and three paths through the maze, each with its own costs, risks' and benefits.

5. The Window of Opportunity at the Strategic Decision Point: what you do in the next five years will position your organization respective to competitors well into the next century. See where you've been and one view of where you're going; choose your next steps.

Sidetrip B departs here: (see page 32) if you chose to make the move to the new territory, your route would take you through the major states of change. You'll get an overview of events, challenges, and opportunities in each state.Guide to Executive Roadmap

New-territory organizations are characterized by high commitment, by lean, flexible structures, and by results that are 30 to 50 percent better than similarly equipped, traditional organizations. These new-territory organizations are changing the way we organize ourselves.

Take a look around traditional territory. Notice the culture. The management style may be paternalistic, autocratic, participative, or inspirational. Regardless of style these organizations are designed to maintain control over people, usually through some combination of top-down power and roles and rules.

These forms of control, perfectly appropriate when first invented, are now limiting and even dysfunctional. The current crisis in so many American industries attests to that. For many organizations in certain industries, the issue is survival. For agents of change, the issue is how to organize to ensure not only surviving, but thriving in this increasingly chaotic business environment.

The commitment-based organizations we looked at have evolved ways of getting their members to pull in the same direction without resorting to control tactics. The transformation projects have a variety of names and themes; the fundamental change underlying most of these projects is the shift from control over people to commitment by people.

We are indebted to Dr. Richard Walton of Harvard University for first identifying the distinction between control and commitment-based organizations.

1. Shortcut to the Bottom Line

The arrow illustrates the impact that organizing for commitment can have on an organization. In terms of business results, traditional organizations range from those on the edge of bankruptcy to the "excellent" companies made famous by Peters and Waterman.

A handful of Commitment-based organizations are discovering that it is possible to move beyond excellence. They have' in many cases, achieved breakthroughs in hard-number results-in other words productivity, quality, and cost. Their soft results- member need satisfaction, individual and organization development, and stakeholder relations-are often even more impressive. The organizations of the future will set new standards in both hard and soft results.

2. Some New Territory Settlers

As the wave of innovative organizations grows, the survival range for traditional organizations will shrink proportionately. Organizations now face the choice of changing to new forms or being swept aside by their more innovative competitors. Commitment-based organizations exist as isolated cells in many corporations. Originally intended as experiments in the art of the possible' these cells have generally flourished in spite of their host systems. Almost all of the original settlers were new manufacturing facilities sponsored by large traditional corporations-the Quaker Oats pet food plant in Topeka, Kansas, and the Sherwin Williams paint factory in Richmond, Kentucky, were two early and highly publicized examples.

The initial successes led to redesign projects in both manufacturing and nonmanufacturing settings. American Transtech's Jacksonville headquarters made impressive gains from the redesign of their shareholder services function. These successes have helped stimulate division- and corporate-wide projects-the latest frontier in the new territory. Procter & Gamble, long a pioneer in innovative plant design, is now looking at corporate-wide transformation. Ford, Champion International, Polaroid, and others also are on this new frontier.

Two Success StoriesThe work at Zilog's Nampa, Idaho, microprocessor plant is clone by teams of technicians, each responsible for a whole piece of the fabrication process. Zilog has no quality contro! ciepartment there are three `'quality improvement resources" available to the teams? who clo their own inspection anci acceptance. The walls are literally papered with process information. Technicians not only know what has to be clone, they also know why.

Chip yields per wafer have generally run 30 percent higher than the competition, using the same equipment and technology. Turnover averages 4 to 5 percent annually in an inclustry where 40 to 50 percent is typical. Technicians use their communication and problem-solving skills at home too.

The breakup of AT&T resulted in the creation of an organization, American Transtech, responsible for shareholder transaction processing. Transtech took acivantage of the corporate restructuring to transform themselves as well. Using the semiautonomous team concept, the members createct a new work design one characterized by high commitment, customer focus, and an emphasis on providing a high-quality product at the lowest possible cost. There are only three levels in the entire organization: the business team, or top management; the management level; and the work teams.

Work teams are trained in finance anct quality and know all the desired outcomes of the company. On-line information systems give the members immediate feedback on the cost of transactions, providing information necessary for continuous improvement.

The results? After three years in operation, procluctivity was up 300 percent, work teams had found ways to reciuce costs by 40 percent, and customer satisfaction was up to very nearly 100 percent as well.

3. Skyline Drive

On Skyline Drive, we compare a typical traditional organization with a hypothetical composite of the best of the innovative organizations we have seen. The comparison is neither extensive nor exhaustive, but should give you a picture of the differences between the two types of organizations.

Culture Based on Control Over People

Organization seen as machine with interchangeable parts.

Functional Hierarchical Units

Technical systems designed by technical specialists; technology determines organization

Structures feature inflexible, fixed jobs; unwieldy role- and power-oriented hierarchy

Information and decision systems designed to serve management needs

People processes managed by the personnel function; thrust primarily administrative

Rewards both intrinsic and extrinsic-encourage "upward focus" and "looking good"

Culture Based on Commitment

Organization seen as a living system

Flow State-Guided Autonomy

Jointly designed with social system described below

Structures flexible, flat, lean, team based, achievement oriented, and sup port oriented

information and decision systems designed to support core work; business information at work floor

The "planting and growing" of people in the organization a high developmental priority owned by the line and sup ported by human resource development expertise

Reward systems designed to reinforce organization vision and objectives and to meet member needs

Disabling DesignController, planner, decision maker, director, coordinator, enforcer, caretaker, supervisor, evaluator, protector of the status quo

Feelings range from comfortable, secure, and satisfied to frustrated, voiceless, fearful, powerless, discounted, anxious, and angry

Most people don't enjoy working, growing, being challenged, or being responsible, it's management's job to motivate and control their performance and behavior

Some people have potential-most don't

It's cost effective to design jobs that require minimum skills and flexibility

More and bigger is better

Fear and competition among employees are useful motivators

It's important to protect yourself, those above you, and those below you from uncomfortable truths

Enabling DesignBusiness manager, visionary, committed champion of change, strategist, entrepreneur, learner, coach, trainer, developer of others, boundary manager, organizational architect, enabler, creator of the future

Generally challenged, purposeful, powerful, creative, believed, respected, secure, important, trusted, and needed

People thrive on creating, contributing, growing and being responsible when in an environment supporting those traits. It's leadership's job to create and sustain such an environment

We have only begun to tap into our people potential-our greatest natural resource

Investing in flexible roles and broad and deep skills training is one of the keys to unlocking potential

Small is beautiful

Motivation comes from within-from a sense of purpose and commitment

Telling the truth, a radical old notion, is the stuff that organizational breakthroughs are made of

4. Choose Your Path Through the Maze of Change

Major change can be either an unparalleled opportunity or a potential disaster. Your organization's strategic posture makes the difference. There are three doors into the maze of change presented by mergers, quality crunches, and new manufacturing of information technologies

A. Ignore the effects of change on the culture. After all, "we've got real work to do around here'"

B. Adapt the culture in incremental ways that support the changes, such as provide some training in new technologies without changing the old structures or systems affected by those technologies.

C. Create the ideal culture: use the occasion provided by major change to go for an ideal future vision; to redesign and renew the organization.

Major change can be driven by any of these three forces:

> Mergers or restructurings: Most mergers fail because of clashing corporate cultures. The restructuring dilemma: how to build focus, flexibility, and commitment and avoid the hemorrhaging of trust and loyalty while reducing levels of hierarchy.

> Quality crunch: The fantastic news discovered by many Japanese firms in the fifties and sixties and many U.S. forms in the eighties is that quality is a major source of cost savings. The rub: As reported in Business Week's June 8, 1987, special report on quality, "This requires a sweeping overhaul in corporate culture, a radical shift in management philosophy, and a permanent commitment at all levels of the organization to see! continuous improvement."

> New manufacturing and information technology: Transplanting modern technology into outmoded social systems is a frustrating and risky game. On the other hand, joint design and implementation of technical and social systems is a proven path to organizational breakthrough.

The reckoning: Each of the three paths through the maze of change has benefits, costs and risks associated with it. The immediate costs are easy to estimate; the long-range risks less so Tally up your score, and you'll either' return to traditional territory-do no' pass Go; do not collect $200--or finish the tour.

5. Potential Window of Opportunity

The next five years represent a unique window of opportunity for organizational transformation. It is our belief that the numbers of commitment-based organizations will increase exponentially in the coming decade.

We believe that organizations that are not a part of this wave will be left behind.

The writing on the wall: Our competitiveness in the global market depends on our ability to organize ourselves for low-cost, high-quality goods and services. Our innovative organizations have shown us one way that can be done. But we are still at the Model T stage. As good as these organizations are, "We ain't seen nuthin' yet."

Sidetrip A: Ten cutting-edge competencies

The keys to unlocking extraordinary performance and a commitment-based culture are the same ones that can lock an organization into mediocre performance and a control-based culture. Achieving and sustaining extraordinary results requires turning two keys: leadership development and organization design. Having one without the other is like rowing a boat with one oar-lots of activity and motion, but little progress.

Organization design is the skeleton that gives an organization its form and defines its possibilities for movement and performance. Leadership assumptions and behaviors can set the feeling, tone, and direction for the organization. If the organization design is rigid and the collective leadership mindset is closed to new thinking, the result is a culture highly resistant to learning and change. If, on the other hand, leadership is committed to an expansive vision of the possible, and if the organization design supports and promotes that vision, the organization can weave a new cultural fabric that is strong, flexible, and responsive to change.

In commitment-based organizations, leadership is seen through new lenses. Traditional organizations tend to consider leadership and top management as one and the same. Commitment-based organizations know that leadership is a function to be performed at all levels of the organization at various times by any number of people.

Seen through these new lenses leadership competencies take on a different emphasis. Traditional process and functional competencies are still needed throughout commitment-based organizations, but they are no longer limited to specialists and functions. In the' commitment-based organization, tines' competencies are more widely diffused

We identify 10 cutting-edge competencies critical to achieving and sustaining commitment-based organizations Some of these competencies are old' friends, others are less familiar. All o them need to exist in the leadership a all levels of an organization.

Ten Competencies

> Creating shared visions. This is perhaps the most magical and exciting of the competencies. A shared vision, clarifying purpose, principles, and values represents the ideal toward which the organization is always moving and around which it can build or reshape its culture. It's a powerful first step in freeing the spirit and energy in an organization.

Committing to "total quality" in all aspects of an organization's technical and social processes is proving a compelling ideal, challenging members at all levels to quest after the best in themselves. Ford, Xerox, Kodak, Rohm & Haas, and Procter & Gamble are among the many corporations choosing quality as the central theme in their vision of the future. Visioning theory and methods are widely understood.

> Planning and leading transitions. Negotiating the trip from traditional to new cultural territory is a very special logistical challenge. Bringing a vision to life involves living the vision each step of the way: The process for getting there is the process for being there. Some of the challenges of planning and leading transitions are discussed more fully in Sidetrip B.

This competency is never more vital than when the transition involves creating a new culture. And committing to a vision of total quality amounts to nothing less than, as quoted from Business Week above, "a sweeping overhaul in corporate culture ....', Some of the most significant failures in organization change projects have been due to underestimating the planning, time, and resources required to ensure a successful transition.

> Organization analysis. Any successful change process calls for fundamental understanding of root causes and effect: the ability to see how structures, rules, roles, systems, processes, beliefs, outcomes, and environment all affect each other.

A good model will focus on the 20 percent of the controllable variables that affect 80 percent of the results. Our traditional models of organization tend to be both simplistic and misleading. For instance, quality, long thought to be a "worker problem" to be solved by slogans and quality circles, is now seen as a systematic challenge involving all aspects of organization design and culture.

> Technical systems analysis. A specialized subset of organization analysis focusing on the core work of the organization, technical systems analysis details all essential steps required to convert inputs to outputs. It identifies and analyzes the key variances that interfere. This competency helps people set aside functional and specialist lenses in designing and executing core work.

What we call technical systems analysis includes two important bodies of expertise: statistical quality control, based on the work of Deming and Juran; and the sociotechnical systems theory pioneered by Eric Trist and evolved by Lou Davis, James C. Taylor, John Cotter, and others.

The two approaches are complementary: The first emphasizes continuous improvement while the second sets the stage for joint redesign of technical and social systems. Most of the commitment-based organizations in North America have been influenced by the latter approach.

> Organization' design. To attempt to overhaul a culture without adjusting the design holding it in place will create much activity but little progress. To create a commitment-based culture, all organization design choices, including purpose, principles, policies, technical systems, structure, information and decision systems, and people and reward systems, need to support that culture.

A major gap in some programmatic approaches to quality-focused vision is the lack of appreciation for the role of organization design in eliminating or minimizing organizationally generated blockages and creating and sustaining a commitment-based culture. Important pioneers in innovative organization design include Lou Davis, Charlie Krone, and Herb Stokes.

> Learning how to learn. The leading corporations of the future will be those who best develop themselves into learning systems. In addition to traditional training programs, we need to develop and institutionalize effective learning processes. Mastering this competency dramatically accelerates the acquisition of other competencies, traditional and cutting edge.

Learning how to learn lies at the heart of the continuous improvement so essential to a total quality thrust. Continuous improvement uses both doing things right and doing the right things. The quest to do the right things is exemplified by IBM's building of "contention management" into its culture.

> Proactive environmental focus. In a world that is changing at an ever-increasing rate, a proactive environ

mental focus, including reading the environment, tuning into the future, scenario planning, building bridges and alliances, influencing hostile environments, and developing collaborative relations with stakeholders, is essential to keeping ahead of the game.

Creating a culture of total quality generally involves radical changes in working relationships with both suppliers and customers. The ideals of "zero inspection of incoming materials" and "100-percent customer satisfaction" are beginning to show up in practice as well as in vision.

> Process facilitation and design. These capabilities are necessarily woven into all aspects of a commitment-based organization. Not only meetings, but all recurring interactions between people can be designed and managed to be purposeful, effective, efficient, and energizing.

For a striking introduction to a commitment-based organization, sit in on a technician team meeting. You'll usually find a level of openness, candor, and general meeting management skills that would look good in any management committee meeting. These competencies don't just happen; they reflect a strong commitment to developing high levels of social as well as technical skills.

> Empowering self and others. Experts agree that we use only a small fraction of our potential. To achieve our full potential we need to move past the inner constraints and limiting beliefs buried in our subconscious. Empowering self and others focuses on breaking through those inner constraints.

Many training programs, mostly aimed at individual development, are available. While the initial impact of many of these programs can be dramatic, it is important not to rely on individual empowerment alone as a cultural change strategy. The changes in individuals need to be supported and sustained by a committed leadership and an enabling organization design.

> Context design. Context design goes beyond empowering self and others. It is a different level of technology-one based on language distinctions rather than processes. For instance, Deming's insistence that each employee, including the CEO, identify his or her immediate customers and commit to meeting the expectations of those customers is a powerful example of shifting context. Context design is a technology based on linguistics and ontology designed to facilitate organizational breakthrough.

The major states of change were first explored by Richard 13eckhard and Reuben Harris. His transition planning model neatly defines the work of each stage and the plans and activities that accompany them.

The traditional approach to organizational change is problem driven; the focus is on the current state and what's wrong with it. While that approach may seem logical, the problem is that starting with what's wrong today tends to limit one's view of the possibilities.

In the organizations we've studied that have been most successful in transforming themselves, change is vision driven. The transformation starts with the creation of a clear and compelling vision of the ideal future state. If your organization were functioning ideally, what business would you be in? Who would your customers and stakeholders be? How would you organize yourselves to best serve those customers and stakeholders? What structures and systems would you have in place?

Designing that ideal future, through several iterations and in considerable detail, brings the vision alive for the change managers and sponsors. The work begins at the "blue sky" level and gradually becomes grounded in a future reality unfettered by the constraints and problems of today.

With the endpoint of the journey so clearly defined, we then return to the beginning. Given the ideal future you have so clearly sketched for yourself'

what needs to happen today in order to make that vision a reality? Some things can be changed almost immediately; others take a bit longer and will have to go through stages. Analyzing the current state in light of the ideal future state brings the transition plans into focus. Planning and leading the transition then becomes a journey into familiar territory; not a bold venture into the unknown.

The artistry in planning and leading organization transitions lies in charting the path from the current state to that ideal future state. This usually requires the creation of parallel organizations, transition managing structures, and reward and information systems expressly devoted to the unique needs of the transition states. And just as the future state is designed to be an expression of the ideals and values of the organization, so the transition states must also reflect those values and ideals. When properly designed and managed, the transitions are a rehearsal for the new organization: The process for getting there is the process for being there.

Transition journeys often jump their tracks due to an underestimation of the size of the task and the resources required. Even under ideal conditions, the best-laid plans can go awry. Contingency planning, parallel organizations, and slack resources can all help ensure a successful journey into the new territory.

Envision the ideal future state

Challenges: How to

1. Create a corporate vision that

- clarifies business mission;

- goes for breakthrough and is not constrained;

- focuses, aligns, and empowers;

- is owned by the membership and other stakeholders;

- protects strengths of existing culture;

- and provides an umbrella to unit visions.

2. Develop ideal designs that will best support those visions.

3. Balance organization-wide versus unit decisions.

Ideas

1. Learn from commitment-based organizations.

2. Ensure that visioning and broad designing is informed by

- sound strategic business focus;

- emphasis on creating synergy between management and labor;

- technical and social systems;

- new information technologies and everything else;

- all units and their customers.

3. Be willing to change anything.

4. Hammer out those vital few principles that can replace pounds of rules.

5. Set "impossible" goals to facilitate breakthrough thinking.

Analyze the current state in light of the ideal future state

Challenges: How to

1. Equip leadership with lenses that provide a systemic and objective overview of their organizations.

2. Distinguish root causes from symptoms.

3. Identify which design elements and managing assumptions are locking the existing culture in place.

4. Select key leverage points to maximize the domino effect.

Ideas

1. Design events and activities that break down barriers between levels and functions and ensure that the top can clearly see the organization through the eyes of workers as well as their own;

- use cross-functional teams to create integrative outcomes.

2. Use technical systems analysis to help break down barriers between levels, jobs, and functions.

3. Do a commitment analysis of the critical mass of leadership.

4. Identify and pick '`low-hanging fruit" on the way to the ideal.

Plan and lead the transition

Challenges: How to

1. Define specific time-bounded change objectives.

2. Develop detailed designs to support those objectives.

3. Ensure balance between managing change and maintaining operations.

4. Provide adequate resources and develop sound implementation plans.

5. Provide time, support, and understanding for the "losses" Implicit in any transition.

6. Deal with mid-management shrinkage and role changes.

7. Ensure top-to-bottom ownership versus top-and-bottom ownership.

8. Honor how you got where you are. 9. Work with, not against, resistance.

Ideas

1. Challenge individuals and units to breakthroughs.

2. Explicitly design each activity in a way that brings the vision to life.

3. Provide resources and support in a way that empowers without building dependency.

4. Create a framework and support that stimulates guided autonomy in the transition and target cultures.

5. Develop an education strategy that builds and spreads learning capability.

6. Ensure that reward systems and temporary structures fully support transition success.

The executive role

Challenges: How to

1. Break free from limiting assumptions.

2. Create a leadership vision out of its commitment to action.

3. Create a broad strategy that

- is success oriented;

- is highly leveraged;

- ensures sustaining momentum and accountability;

- provides for continuous learning at all levels;

- demonstrates the target culture.

4. Develop the special competencies required to lead the change effort.

5. Build stakeholder commitment to change, demonstrate continuity of leadership commitment, and create a communications strategy that

- demonstrates the vision;

- minimizes uncertainties;

- builds realistic expectations.

Ideas

1. Use corporate-level visioning, designing, and planning tasks as vehicles to build executive-level competencies.

2. Charter a cross-functional strategy group to learn the state of the art and to propose ideal organizing forms and concepts for the nineties.

3. Plan for diffusion from the start.

4. Modify reward systems to reflect change priorities.

5. Allocate internal and external resources in a way that

- helps break out of existing mindsets;

- stacks the deck for success.

6. Walk your talk-at all levels, at all stages.