Rethinking IDS From The Bottom Up

Business Week - February 8th, 1993 - By David GreisingPlagued by high turnover and facing new rivals, the top financial planner plans a grass-roots makeover

Becky Roloff never intended to turn her company inside out. One night two years ago in her living room in Bloomington, Minn., the IDS Financial Services vice-president was leafing through a 15-page internal company report about the high level of employee turnover. What she read was nauseating in its lack of insight. "My stomach hurt," she recalls.

To Roloff, the superficially treated attrition problem would eventually rot from within the nation's leading financial planner, whose employees prepare plans for clients and sell them IDS' mutual funds, insurance policies, and annuities. IDS was extremely profitable and growing rapidly as it is today. But, combined with other woes, such as a mistake-prone back-office operation, IDS' high turnover could prevent the Minneapolis-based company from beating back a growing host of new competitors and threaten its position as the standout performer in the ailing empire of parent American Express Co.

Several days later, a fired-up Roloff and another irate colleague, retail banking Vice-President Bill Scholz, tromped into IDS President Jeffey E. Stiefler's office and demanded that the company be overhauled totally. They wanted to set up a "design team," recruited from IDS' grass roots, to consider everything from financial planners' commission structure to back-office operations. Roloff, who heads IDS' insurance-products operation, told her boss: "You're not going to get any work done until you listen to us. We're not going to give up."

Stiefler had to admit that IDS faced serious challenges. IDS Financial Services Inc., with 6,776 planners, once had the field to itself with its innovative, computerized approach to retirement planning. But the future is filled with competitors such as Merrill Lynch & Co., which has converted legions of brokers into financial advisers and written 40,000 financial plans in the last two years, and Prudential Insurance Co., the nation's No. 1 insurer, which is making similar moves. IDS can't compete if it continues to see only 30% of its planners last more than four years with fully half of each first-year class bailing out. What worked in the past, Stiefler figured, won't work in the future.

Wrenching

Over time, Stiefler bought into Roloff's entire idea. The result: IDS 1994, a comprehensive redesign of the company, is set to roll out next year, the 100th anniversary of the former Investors Diversified Services. Before it's done, the redesign could cost $1 billion over four yearsto be reallocated from elsewhere within IDS, assuming that it promises a 2070 return to IDS. The overhaul is perhaps the most far- reaching, as well as wrenching and risky, ever attempted by a major financial-service company.

IDS planners will still soft-sell retirement planning and hard-sell the IDS family of investment products. But virtually all other aspects of how IDS works will be reconfigured. The goal: a force of planners who are smarter, more organized, more plugged into sales prospects, and better supported by the home office (table). Instead of flailing about on their own, planners will get backing from teams of experts on investments, estate planning, and tax planning who will share in commissions. Rather than wasting time cold-calling couch potatoes who curse and hang up, they'll mine referrals from outside accountants and lawyers. Meanwhile, back-office improvements will make the process flow smoother. Plus, if AmEx approves a name change to American Express Personal Financial Planning, planners can more easily solicit AmEx card members.

The IDS makeover is a case study of how Corporate America can and should identify weaknesses and fix them before they really hurt. It also demonstrates how change can bubble up from within the company and how top management can overcome hidebound concepts of privilege, listen to subordinates' warnings, and heed their prescriptions.

If the plan works, it could serve as a model to revamp AmEx. "IDS represents for the whole company a very important laboratory for organizational change," says AmEx President Harvey Golub, the former TDS chief tapped on Jan. 25 to be AmEx' next CEO. He has kept tabs on the design team through monthly meetings. Beyond that, the IDS overhaul could lead to similar transformations at other financial- services companies, whose resistance to structural change is notorious. Since revolutionary thinking swept through manufacturing and retailing in the 1980s, why should banks, insurers, and brokerages be exempt?

Indeed, there have been modernizations at some financial outfits, such as J. P. Morgan & Co. and AT&T Credit Corp., but nothing on the scale contemplated at IDS. "We've seen a movement from the materials factory to the paper factory. Now, we're starting to see movement from the paper factory to the knowledge factory," says David Nadler, president of Delta Consulting Group Inc. in New York, who isn't involved with the IDS revamp. "IDS is the natural evolution, the next step. The size and scope of [the redesign] is unprecedented."

Impractical?

Certainly, the plan may fail horribly. It seeks to change an entire corporate culture that is based on independent salespeople. Asking them to share commissions with experts may look good on paper but prove impractical in the field. Prudential has found that insurance sales reps aren't eager to refer prospects to its Prudential Securities Inc. subsidiary for stock-buying.

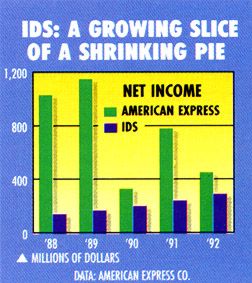

And there's the question about whether it makes sense to tinker so violently with success. IDS has posted average annual earnings jumps of 22'% since AmEx bought the company in 1984, and assets under management have nearly tripled, to more than $65 billion. The typical IDS planner handles client assets of $3.8 million, up 75% from 1984. In 1992, IDS became AmEx' most profitable division, eclipsing flagship American Express Travel Related Services Co., the limping charge-card and travelers-check business, which posted a $342 million restructuring charge. Yet IDS President Stiefler believes that, because of the threat of rapidly growing competition, his company must embrace the new concept: "You can't fall in the trap of doing what you've always done."

The back-office computerization and streamlining will be relatively simple, if costly (eating up $150 million). Today, staffers correcting paperwork mistakes fill an entire floor of IDS' building in downtown Minneapolis. What's more, says Stiefler, as many as 70 of the 110 steps involved in registering a new client are redundant. The result: client complaints and lost time for planners trying to sort out the problems.

But solving the attrition dilemma is IDS' biggest challenge. To be sure, IDS is hardly alone. The problem at many other financial-service companies is as bad or worse. But turnover hurts IDS more than it does such better-known competitors as Merrill and Prudential. The direct cost: half of the $100 million per year in training expenses for employees who don't stay long. Indirectly, turnover means lost business and even more client ill will. "When I took over someone's clients, I'd tell them I would stick with them," says Erich Peterson, an ex-lDS planner from Springfield, Mo. "They'd roll their eyes and say: 'Sure, that's what the last one said.'"

Despite these looming problems, Stiefler was skeptical when Becky Roloff first stormed into his office on the 29th floor of the IDS Tower. An overhaul might be needed, he allowed. Even under Golub, the company had considered such a task. But turning the process over to underlings sounded risky. Stiefler believed a redesign should be run by the president's office. "Being an impatient fellow, I wanted a top- down approach," he recalls.

Stiefler agreed to reconsider her suggestion at a meeting the next day. Roloff, Scholz, and Paul Gustavson, a San Jose (Calif.) consultant who had worked with IDS, spent the night developing a proposal.

Luckily for them, the person to convince was Stiefler, not the sometimesoverbearing Golub. Stiefler, 45, Golub's handpicked successor at IDS, is more open to subordinates. "Harvey is intimidating because of his intellect," says George M. Perry, vice-president for corporate strategy. Stiefler went for the new proposal.

Two weeks later, IDS' senior management gathered at Pecos River Learning Center in New Mexico. IDS 1994 was under way. More than 800 employees responded to an invitation, presented in a slickly produced videotape, to join the 30person design team that would recreate every aspect of how IDS does business. Chosen from throughout the ranks of IDS planners, headquarters staff, and field executives, the design team first met in January, 1992.

The team was to focus on four key objectives: retaining 95% of clients, retaining 80% of IDS planners through four years of service achieving annual revenue growth of 18%, and bolstering IDS' position as the industry leader.

Hot Debate

The team had one major immediate glitch. After the first meeting, several members noticed that there were only two ethnic minorities and no A*ican-Americans. After a hot debate, the group voted to consult with a companywide "diversity committee" to study IDS' inability to attract and retain minorities as employees and clients.

For the 30 design-team members, it was a heady time. During the next year, they alternated weeks in Minneapolis with weeks in their regular jobs. At Pecos River, consultant Gustavson led a retreat that included negotiating rope bridges over rivers, cliffjumpmg, and pole- sittingall to help team members understand the concept of interdependence and teamwork. "I'll come cleanI wasn't a huge believer in some of that early stuff," says John Hantz, a division vice-president from Livonia, Mich. "I sat back in some of those meetings thinking: 'When are we going to get to work?"'

By July, the design team took to the field, logging more than 1,000 airplane flights over a three-month span. They cries-crossed the country, benchmarking procedures in a variety of industries, from computers to manufacturing to retailing. They called on Motorola, Microsoft, Wal-Mart Stores, Nordstrom, and dozens more.

During spring and early summer, the team conducted a thorough "technical analysis" that traced every step of a client's experience with the company and sought to identify paperwork bottlenecks. Interviewing planners, management, and staff, they conducted a "social analysis" of the organizational makeup of the companyconcentrating on problems between planners and headquarters staff. The team sought suggestions through employee phone-a-thong, via computer and fax. And they kept the entire company apprised of their work with a regular newsletter.

The exercise began to wear thin on some IDS employees. "I don't know about you, but I'm tired of hearing about the design team," an exasperated Anna Newcombe wrote to the employee newsletter. "I'm tired of getting copies of their self-congratulatory journal entries that seem reminiscent of children at a playground screaming: 'Mommy, Mommy, look at me!'"

By November, the design team broke up into 10 committees and locked itself into a week of marathon meetings in a suite of conference rooms across the street from IDS Tower, hammering out design recommendations in time for a mid-December presentation to Golub. Posters on the wall exhorted them with sayings such as the Gan&ian "Be the change you're trying to create." In rooms littered with five- gallon bags of popcorn, soda cans, and discarded not~ paper, the committees discussed their "design choices." Memos, suggestions, and inquiries circulated among the groups over a network of laptop Macintosh computers.

Rookie Relief

The final design recommendations won't be unveiled until mid-February. Once approved by senior management, they'll be tested throughout the company this spring. The attrition problem will be hit head on. One likely approach: Rookies will get a year- long, salaried traming period during which they will shadow successful planners. Veterans will be compensated for serving as "mentors" to rookies.

To attract and keep clients, the design team recommends a more focused approach. Cold-calling is encountering increased public resistance. As an alternative, IDS will use "centers of influence"referrals from outside professionalsto find prospective clients. Plus, reformulated paperwork and enhanced computer technology will reduce errors and streamline communication.

A full rollout of the design team's recommendations isn't due until 1994, but some ideas are already in the field. Homer Nottingham, a Ventura County (Calif.) IDS planner, is giving a workout to design-team recommendations on lead generation, teamwork, and work- force diversity. He has encouraged more teamwork among his planners and aggressively attacked the diversity problem. In six months, he has doubled the number of women, to 22, and half of his current class of 50 new recruits are ethnic minorities. "It's bringing in great teamwork, and we're working as a unit now," says Nottingham. "The design team has opened our minds." Assuming this all worksfar from a sure thinga closely watching Harvey Golub may use it to open minds at American Express, too.